Somewhat Better Outcomes With Longer-Term Treatment For Opioid-Addicted Youth

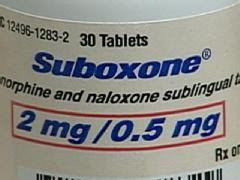

New research published in the November 5 issue of JAMA reveals that long-term therapy rather than short-term therapy for opioid-addicted adolescents yields better results. Those who received continuing treatment with the combination medication buprenorphine-naloxone were less likely to test positive for opioids and reported lower rates of opioid use compared to adolescents who participated in a short-term detoxification program with the same medication.

Adolescents tend to abuse opioids in the form of heroin or prescription pain-relief medications. Recent research suggests that more and more young people are abusing these types of drugs, and therefore treatment needs are rising as well. "The usual treatment for opioid-addicted youth is short-term detoxification and individual or group therapy in residential or outpatient settings over weeks or months. Clinicians report that relapse is high, yet many programs remain strongly committed to this approach and, except for treating withdrawal, do not use agonist medication [drugs that mimic the effect of opioids by altering the receptor]," write George Woody, M.D. (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) and colleagues.

To compare outcomes of opioid-addicted adolescents who receive either short-term detoxification or long-term treatment using buprenorphine-naloxone, Dr. Woody and colleagues conducted a study with 152 patients, 15 to 21 years of age. The long-term treatment medication consists of an oral medication that relieves symptoms of opiate withdrawal (buprenorphine) and a drug that prevents or reverses the effects of injected opioids (naloxone). Patients who were randomized to receive the 12-week buprenorphine-naloxone treatment received up to 24 mg. per day for 9 weeks and smaller amounts through the twelfth week. The remaining participants (the detox group) received up to 14 mg. per day, with doses tapering off through day 14. Individual and group counseling was offered to all participants.

Wood and colleagues found that at weeks 4 and 8, the detox group had a higher percentage of opioid-positive urine test results. Specifically, after 4 weeks, 61% of participants in the detox group had opioid-positive urine test results compared to 26% of participants in the 12-week buprenorphine-naloxone group. The figures after 8 weeks were 54% positive in the detox group and 23% positive in the 12-week buprenorphine-naloxone group. By the twelfth week, the buprenorphine-naloxone group had been tapered off of their treatment and 43% tested positive for opioids compared to 51% of detox group patients.

About 21% of detox group patients and 70% of buprenorphine-naloxone patients remained in treatment by week 12. Patients in the 12-week buprenorphine-naloxone group reported, during weeks 1 through 12, less use of opioids, cocaine and marijuana, as well as less injecting and less need for additional addiction treatment. Both groups measured high levels of opioid use at follow-up.

The authors clarify that, "Taken together, these data show that stopping buprenorphine-naloxone had comparably negative effects in both groups, with effects occurring earlier and with somewhat greater severity in patients in the detox group."

"Because much opioid addiction treatment has shifted from inpatient to outpatient where buprenorphine-naloxone can be administered, having it available in primary care, family practice, and adolescent programs has the potential to expand the treatment options currently available to opioid-addicted youth and significantly improve outcomes," conclude Woody and colleagues." Other effective medications, or longer and more intensive psychosocial treatments, may have similarly positive results. Studies are needed to explore these possibilities and to assess the efficacy and safety of longer-term treatment with buprenorphine for young individuals with opioid dependence."

David A. Fiellin, M.D. (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.) writes in an accompanying editorial that more evidence is necessary in order to claim any treatment is effective for opioid-addicted individuals.

He concludes that: "The results of this trial should prompt clinicians to use caution when tapering buprenorphine-naloxone in adolescent patients who receive this medication. Supportive counseling; close monitoring for relapse; and, in some cases, naltrexone should be offered following buprenorphine tapers. From a research perspective, additional efforts are needed to provide a stronger evidence base from which to make recommendations for adolescents who use opioids. There is limited research on prevention of opioid experimentation and effective strategies to identify experimentation and intercede to disrupt the transition from opioid use to abuse and dependence."

___________

source: MediLexicon News

Turn Over A New Leaf...

Turn Over A New Leaf...